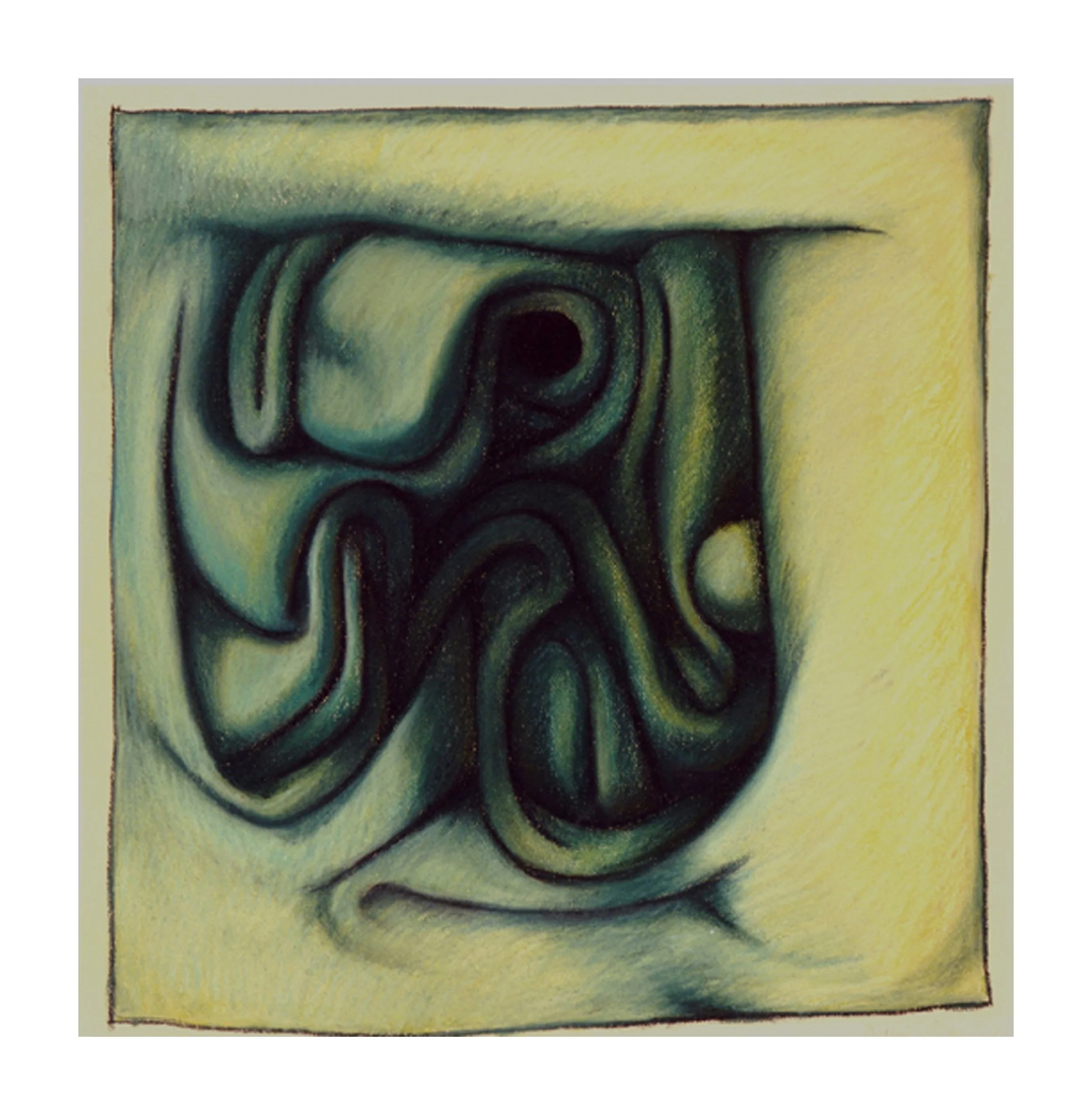

Daria Gan

Brainstorm

1969

120 cm x 180 cm

Dry pastels on paper mounted on canvas

Last Man on Mars

The ship sways slowly and silently somewhere in the middle of the Indian Ocean. The huge moon, orange, nearly red, hangs like a heavy belly in the sky. Swarms of flying fish, with their silvery wings, flip around and dive into the waves. They are playing with millions of stars.

Deck six in front of the ship is silent and dark. The men, above, in the captain’s bridge, must be able to see, what is in their way.

Starry Night

I am lying with arms outstretched in one of the darkest corners of this deck. The boards are still warm here.

On the other side, a door opens, and two people come out. Both seem to be frail, quite old. Their hair in the moonlight is pure silver. The man lifts the woman`s face with both hands and kisses her cheeks. She takes a picture or two. Then they discover the stars and stand there, in the middle of the bridge, holding the railings. Silent and starstruck.

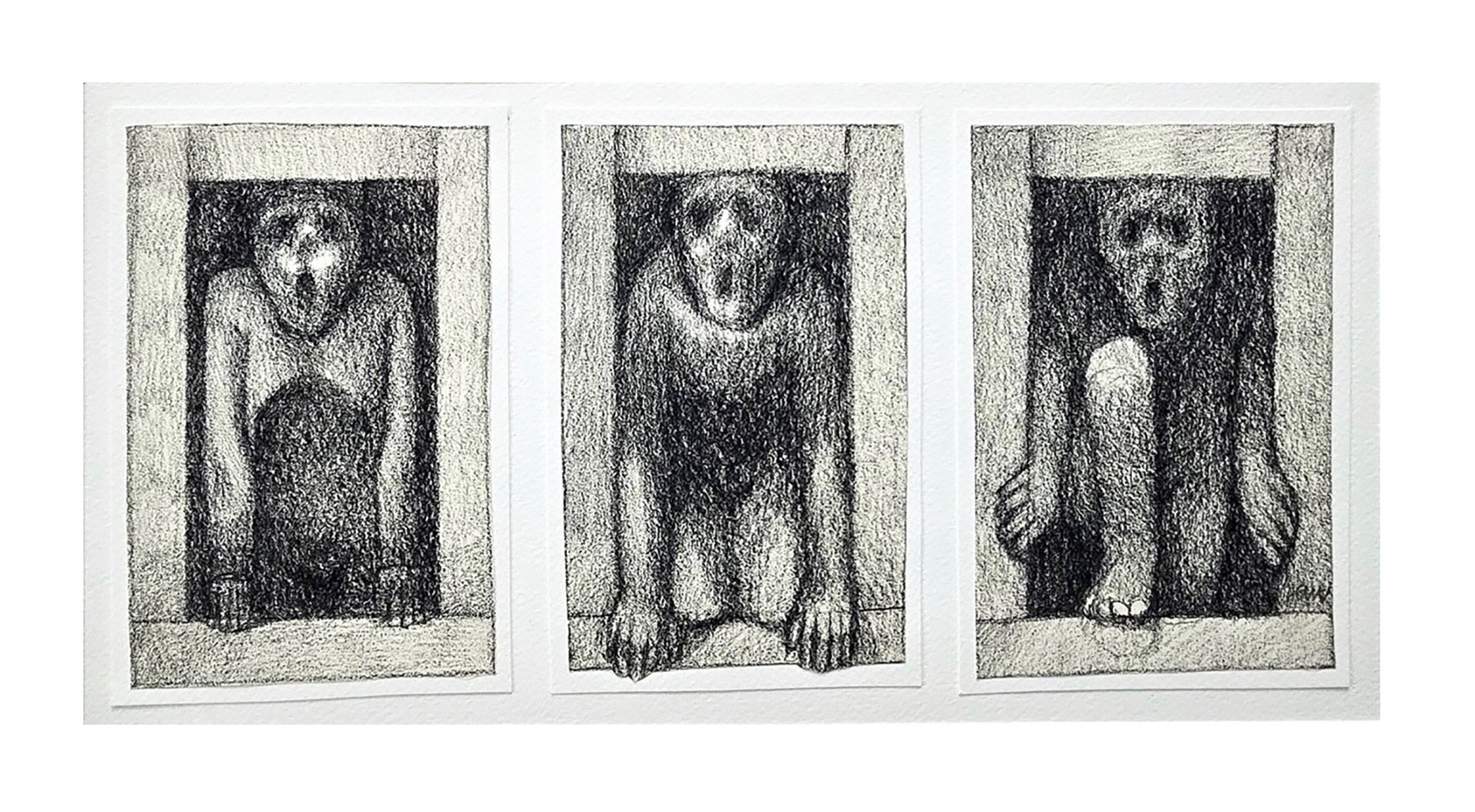

Big Brother

I did not get much sleep that night. The alarm clock rang, as always, at ten minutes to five. I got dressed, put my little daughter in the stroller and deposited her in the kindergarten round the corner.

In our street, every two to three hundred meters, stood an armored car. The howitzers, raised high, were aimed at our homes.

In front of the administration building there were many more of them. Heads of men in green uniforms protruded. Cigarettes hung from the corners of their mouths. They looked unwashed and tired.

I stamped my card a few minutes before six and started my usual daily rounds. Men in protective suits and asbestos gloves poked into small tapholes of the blast furnaces. The molten iron and the slag had to be liberated and directed into enormous, insulated train carriages. I admired the men’s calm and skillful movements. I was supposed to write an article about them for our company´s weekly newspaper.

Back in the office we were told that on leaving work, everybody´s identity will be checked by the green men. All documents must be ready.

The Green Men

How often men in civilian suits stopped me somewhere in the city and asked to see my citizen´s card. They usually looked into my shopping bag as well. Since my daughter was still small, I was allowed to have one and a half rations. Five hundred grams of carrots for me and two hundred and fifty grams a week for her. Three hundred grams and one hundred and fifty grams of bread a day. Two hundred and fifty grams of margarine a week for me and hundred grams for her.

Sometimes I had no carrots left. I gave them to the saleswoman who hid a pair of socks under the counter for my daughter. That´s what everybody did in our country.

Four green men stood at the gate. One of them took my ID, scribbled something on it and threw it in a large wooden box.

I am to be in front of my house at five o’clock tomorrow morning. With my daughter and a small suitcase with the necessary things.

It went so fast that I had no time to say anything.

Something similar happened already once in my life. Then, twenty-six years ago, there were the black men. They also came at night.

At dusk, men were loaded on trucks first. Then women, old people and children. They were never seen again.

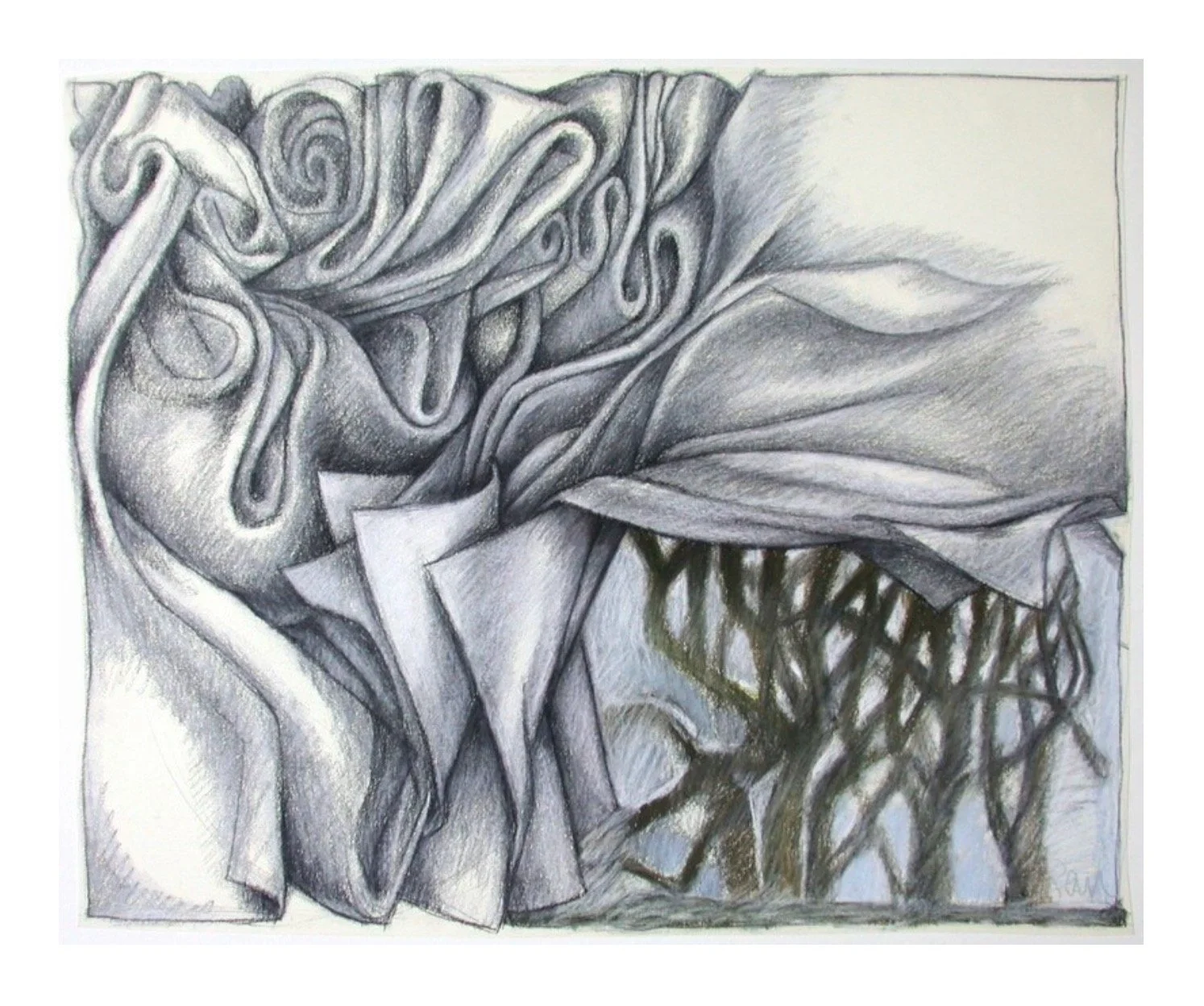

War with the Newts

Who Will Come Will Come and Who Will Have to Go Will Go

Those who are to come will come. They are already close.

In a hundred years, people will carry burdens on their shoulders again.

Those who achieved more will ride high on their horses.

We will be able to die earlier.

Plagues will overwhelm us. Thin us out. There will be more space everywhere. The air above our dwellings will be clearer and sweeter. People will stop measuring it.

Research will be banned; all will be blown up.

Devil´s work.

Museums and theaters are already piles of rubble on which scrub is now growing.

Music will be made at home. Songs will rise into the night.

One will be able to hear birdsong again and surrender to fate and death.

In God´s name.

The Other Shores

A small village in the desert. All houses look the same, built of bleached sandstone. The street is endless and deserted. No trees, no grass, no birds.

I am sitting at a small marble table in a shady tearoom, my travel bag next to me. Not far, wrapped in layers of fabric, a youngish looking woman is chopping fresh vegetables.

A beautiful day, she says.

A little bit of rain would do good, I answer.

A man behind the bar tries to light a hand-rolled cigarette.

Can I stay here for a while without ordering anything, I ask. I can´t pay, I don’t have any money left.

Is no one coming to pick you up, the woman asks.

A Bed for Tonight

No, I came on the bus. My money lasted only this far. I am looking for work, cooking, cleaning, writing letters. In other languages too.

Where are you going to sleep tonight, the woman asks again. She looks at me a little longer now.

After a while she turns to the smoking man.

Luigi, she says, signora could sleep next to your nonna tonight. If she thinks it is the right thing, she could stay for a few more days until she has found a job.

She turned to me, to see if I agree.

Of course I did. I wanted to thank her but could not speak. Tears overwhelmed me.

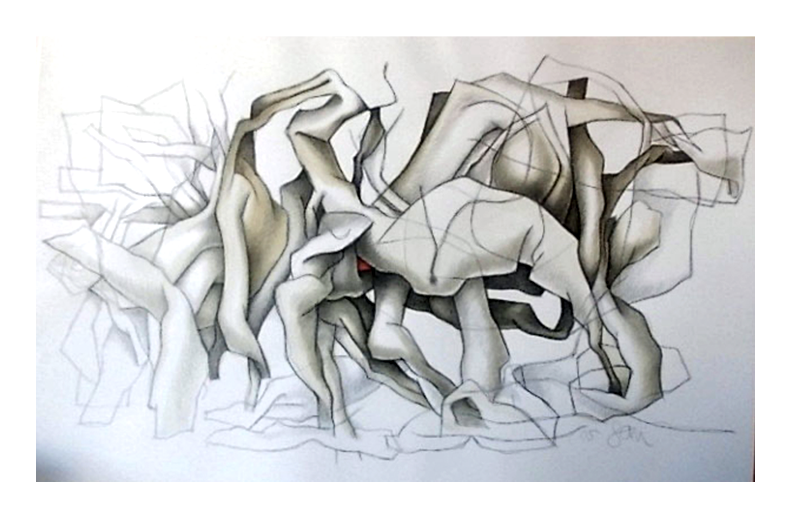

Wargames and Wastelands

It was in Lviv in 1943. I sat next to my mother in a huge dark hall. On the stage a fat woman in a dark red velvet dress was screaming and hopping about. Shots were fired, she screamed even louder, jumped over a low piece of wall and was gone.

This was Tosca. The lady in the velvet dress, the one who sang. Our neighbor. From the apartment above, said mother.

Soon we could not go anywhere anymore. After sunset heavy bombers arrived. Our house was near the Lviv railway station. We lived for weeks in the cellars.

Tosca

During the day, however, it was mostly quiet. We children could go to school and in the afternoon play in the courtyard under the cherry tree.

Once, when I came home from school, many neighbors stood in the stairwell and stared down. There lay a fat woman in a white nightgown.

She jumped to her death, mother said. Poor dear Tosca. Because of the bombs the opera house had to close, and she had nothing to eat any more.

To The Child Never Born

It started in the last week of July. Hot cosmic winds dragged scorching fluorescent shimmer into the earth´s atmosphere and tore it apart. People found this show fascinating at first.

The gleam in the air looked beautiful. The mountains were mother-of- pearl blue, the cooled down dust in the streets and on roofs mother-of-pearl green. But then most computers came to a standstill. Lights went out, everything stopped. Many natural deaths were registered.

The Heatwave

Two months later gynecologists sounded the alarm. No new pregnancies were reported. Not in Karakorum, Belize or Niederbipp. Nowhere.

Everybody started to comprehend, that we, our children and grandchildren are the last ones on this planet.

Selfies

My bus disappeared round the corner. I asked the woman, who sat at the bus stop, if she knew why they closed the discount store on the other side of the road.

Nix German, I Serbia, she answered.

She loosened her shawl and showed me a pinkish red, barely healed scar all around her neck. She followed the scar with her fingers.

I hospital, no dead. She looked at me, not quite sure if I understood what she wanted to say.

Husband no pay, bad men make me kaputt.

If I got it right, her husband in Serbia did not pay the “decimo.” They found his wife in this small German town and cut her throat. Not deep enough though.

The next bus arrived. When she got off in the town center, she winked and smiled at me.

Nix German

Wash Your Mouth Next Time

A woman at the supermarket checkout point turned her head. Wash your mouth next time, she said. You smell of onions.

I really did have something with raw onions for lunch. It was a pitta wrap at the Turkish kebab place for two Euro and eighty cents.

Her words frightened me. People in the line behind me must have heard it too.

I have learned by now. It is better to be careful when I have to be too close to people from here. I always step down from the sidewalk and let everybody pass. Especially if they have a big dog with them. I don´t want to be hurt.

And I never quarrel. When they think they are right, I bend my head and move away, without saying a word.

Before the end of the winter heating season, when the owner of my apartment comes to read the amount of heat I used, I hide all books in my own language. If he spotted them, he would look at me in a different way. My place would not be the same anymore. He might still shake hands but would not look straight into my eyes.

Daria Gan